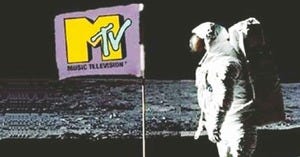

Video Killed the Radio Star

AI is going to make the specialist unnecessary. All hail the generalist.

Aswath Damodaran is a well-respected NYU professor. He teaches financial valuation at the business school. He is articulate and excellent at explaining technical things in simple, elegant terms. He’s very accessible. He has a website, of course. But there are also YouTube videos and newspaper pieces. That’s table stakes. In my opinion, he has elevated himself above the crowd of his competitors by being willing to put his reputation at risk. He publishes analyses of companies, including valuations. He has skin in the game.

Last week, he wrote an intriguing essay for the Financial Times on AI.

Apparently, there is a “Damodaran Bot.” Naturally, he heard about this from a professor friend. The bot has “read everything that I had ever written, watched every webcast that I had ever posted and reviewed every valuation that I had made public.”

Here’s the tricky thing. The bot was ready to perform valuation analyses of its own. Damodaran (the man) could then compare the machine’s work product with that of his best students. For him, it was a no-win scenario. Either he’s replaceable or he’s a bad teacher.

He identifies three dimensions of decision-making in which we should frame AI: intuitive-mechanical, rules-based-principles-based, and objective-subjective.

In the case of the first dimension, we can imagine a spectrum along which tasks fall from the entirely mechanical (calculate the product of these numbers) and the intuitive (say, marketing). I know what you’re going to say. Marketing these days is plenty mechanical; there’s a ton of data to analyze. But we can also say that a good marketer is someone with a strong intuition for how to make sense of those numbers and to tell a story that relates those numbers to the very human experience of trying to determine if a product will sell and to whom and for what reasons.

The other two dimensions are self-explanatory. I can either tell the system a set of rules (ironically calling this an expert system) or I can give it a set of principles, instructing it to make decisions that do not violate these philosophical limitations. We can think of problems in which different people can arrive at the same answer determined by some objective truth and others in which the same people would arrive at divergent conclusions based on their personal experience, values, knowledge, etc.

This framework is as good as any for judging AI. He has several conclusions, but there are several that are germane to our work to understand bureaucracy and to try to make predictions about its future direction.

“First, in a world of specialists operating in silos and exhibiting tunnel vision, AI will empower generalists, comfortable across disciplines, who can see the big picture.”

What is a bureaucrat, we are told, if not an expert, a specialist in some narrow discipline with little to no experience of the whole? We turn to people like Dr. Anthony Fauci when there’s a pandemic because he has the specific knowledge of what the disease is, how it works, what it can do to us, how it spreads, etc. The corollary of this is that we shouldn’t expect him to be capable of a holistic ability to integrate this deep, siloed knowledge with knowledge about everything else including the economy, teenage anxiety, international relations, politics, etc. We wouldn’t ask him to run the country. We have elected officials to do that. (Now, if they defer to him to make decisions about the whole, that’s another story.)

Damodaran is startling here. If the bureaucrat is an expert and we can program a bot to replicate that expertise, then why do we need the bureaucrat? He’s correct that generalists will be ascendant again in a way that our STEM-obsessed, business-school-fixated culture may not yet understand. Give me an intelligent, curious, well-spoken graduate with a philosophy-math double major and a winning smile and she can be anything, do anything.

Second, he distinguishes between mechanical valuations in which you take the historical data and extrapolate it into the future (something we can teach a machine to do easily) and those assessments that quantify a story in projecting the future financial statements for a company. The bots do not have the imagination or the intellectual breadth for story, at least not one we would put our faith in by investing because of it. Story requires judgment and the ability to distinguish the relevant elements from the irrelevant ones in a complex tapestry of facts and theories.

Third, he hasn’t seen any indication of AI’s capacity for epiphany, especially the kind that comes from connecting things that seem disjointed on their face. Generative AI constructs a galaxy of context, but it hasn’t been able to bend this space and time in the kind of idea synthesis humans can. You could put Sir Jony Ive in a machine and you wouldn’t be able to replicate his genius, even if you could simulate an email he might write.

Damodaran writes from the perspective of someone seeking protection from the AI storm. This means finding a place in his three-dimensional matrix where the machines cannot play: intuitive, principles-based, and subjective work. Let the machines take care of the expert drudgery. Extending such logic to the bureaucracy, fortune favors the broad. Most of the people (but not all of them) who populate our agencies are anything but. Could we automate the civil service?

What a time to be alive.