Human beings weren’t built for uncertainty.

We crave the deterministic relationship. We want to know how everything fits together as if it were part of a machine. We want to be able to predict how things will unfold without doubt.

Y = mX + b

Yet, life is messy. Instead of the straight line that we think we’ll obtain, we see a bunch of data points that look like they may be related.

Consider for example, a two-by-two graph of Manhattan apartment prices in dollars per square foot Y mapped against apartment size X. We might expect a linear relationship in which dollars per square foot is positively related to the number of rooms. There is some base level price, the intercept b, that we need to pay for the privilege of living in the heart of New York City. So, we collect a set of reported transactions and make this chart.

If it were a deterministic relationship, then we would expect everything to line up cleanly. Instead, we see points all over the place.

This is because there are many dimensions to trying to explain or predict prices. An apartment in Harlem may have a different market than one in Chelsea. Or it could be that pre-war buildings trade at a premium. It may be a function of the recency of the apartment’s renovation. There are any number of factors that we should incorporate in our understanding.

We can make an educated guess what our assumed two-dimensional linear relationship could look like. We draw various lines to see which ones fit the closest. The line that is the best should be the one that minimizes the variability of points observed around it.

We use these kinds of models to predict. The quality of a model is a function of the accuracy of its predictions. Something that is poor at telling me what’s going to happen is a bad model; something that helps me forecast accurately is useful. If I’m looking to buy a place, I want to know what I should pay; I don’t want to overpay. Ideally, I’d like to get a bargain. But I need to have a sense for what is expensive and what is not.

There are all kinds of dimensions to the problem. But a line is two-dimensional. We understand lines. We can visualize lines. We can calculate lines. Analytic tractability attracts our attention.

So far, we haven’t included time as a factor. Real estate prices fluctuate over time. For example, Manhattan prices have languished over the past twenty years compared to the experience we might have expected ex ante, even as (or because) Brooklyn has boomed.

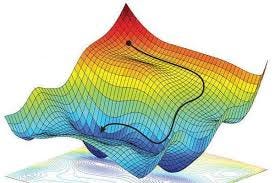

We observe prices at specific dates and then build models for the time series we expect to see in the future. This is a stochastic relationship. We have random explanatory factors that evolve through time, just as the variable in which we’re interested changes. We theorize about the data generating process that underlies our Manhattan prices, relating these variables to the price of apartments. Occasionally, there are discrete changes in the environment that require us to throw out our understanding of what is happening and to come up with a new one.

When Bill de Blasio replaced Mike Bloomberg as Mayor, things started to change. For example, wealthier neighborhoods saw services decline. I once attended a conference at which the keynote speaker, one of de Blasio’s myriad Deputy Mayors, used data to brag about how they had cut rat interdiction in wealthy neighborhoods. That was just one small example of his policies that changed the complexion of the city and its future prospects.

Bureaucracy has a natural advantage over other types of administration in promoting itself. It offers the pretense of certainty. It makes people feel like they can predict outcomes with some degree of certainty. It presents the world as mechanical. Instead, we live in a system in which quantum randomness is inherent from the interactions of billions of people and things. Behavior emerges.

The rules and processes all around us ignore myriad stochastic factors and simplify the world to make it appear static and deterministic and to appeal to our ancient human frailty.

Bureaucracy lulls us into a false sense of security about the world.

Once I think I know the way the system works with its rules and processes, I can feel more comfortable consuming; I don’t need to save as many resources for the rainy day when things don’t go the way I expect.

Unfortunately, the complex adaptive system in which we live doesn’t know this. It evolves through time, indifferent to our simplifying assumptions even as it is shaped, at least in part, by them.

Notwithstanding my assumed certainty about what is happening at this point in time, I do not live in a vacuum. I inhabit a world full of other people making decisions. Over time, the system changes as the impact of these decisions ripples.

If we’re all more comfortable consuming, then we may not have the savings we need as a society to deal with exogenous shocks. We can turn into a nation of fat, entitled, indebted sybarites with an inadequate safety net.

If consumption is the primary, dominant, motive force, we can lose a sense of purpose. We turn to religion and philosophy less as guides for proper living. We abandon time-tested principles of conduct for the relativism of a constantly shifting moment.

We disarm ourselves unilaterally in trade, in immigration, in defense. Our memories of the bad days is attenuated; we fear instead the amplification of the most recent deemed iniquity.

When the exogenous shock comes, and it always does, we are unprepared.

In the West over the past thirty years, we told ourselves that history was over; there would be no more war, or at least anything that would affect us. Go tell that to the Ukrainians. Tell that to Israel.

Our trade theory tells us that there are fantastic economic gains to be had from exploiting comparative advantage with free trade. You are good at assembling iPhones and I am good at financial services. You should specialize in doing that and I should focus on doing this; the gains from our efficiency mean greater plenty for everyone and these will be distributed fairly by reasonable exchange.

What happens if you subsequently restrict my ability to sell financial services to your people? Or my Internet services? Or my anything? I still get cheap iPhones. Shouldn’t that be enough? You get to buy financial claims on my government debt and my farmland and real estate and private sector companies. Aren’t we still better off than the alternative combination of autarky? Will this distortion change other aspects of my behavior over time? Will I become dependent in unexpected ways? Will it perturb the system in ways that weaken us all? Will the money I save on consumer goods distort the fabric of my life in broader not-so-positive ways?

Consumption is an opiate.

There are all kinds of variables beyond just the simple economics of it. Economics is a poor model for the longer term, perhaps.

Maybe, just maybe, there are other factors to consider like meaning and purpose and distribution of income, other human aspects of the problem that manifest politically, but that take time to do so.

As Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said, “Access to cheap goods is not the essence of the American dream.”

The American dream is about freedom and significance and family and friends and independence and security, in addition to prosperity.

Prosperity is necessary, but it sure as hell ain’t sufficient.

In the West, we’ve told ourselves that consumption is great and it is, to a point. But there is more to life than that. We subsidize consumption. We encourage it. We worship it. Consumption brings status. This comes at the expense of other things and these other things have a voice that will be heard, eventually.

The more we suppress these other factors, the more violent their ineluctable eruption into the public conversation.

What does this have to do with bureaucracy?

We live in a complex adaptive system. These systems generate emergent behavior. We cannot control what comes out; we cannot predict it.

“The main idea behind complex systems is that the ensemble behaves in ways not predicted by the components. The interactions matter more than the nature of the units. Studying individual ants will never (one can safely say never for most such situations), never give us an idea on how the ant colony operates. For that, one needs to understand an ant colony as an ant colony, no less, no more, not a collection of ants. This is called an “emergent” property of the whole, by which parts and whole differ because what matters is the interactions between such parts. And interactions can obey very simple rules.”

A big chunk of the way we have structured our economy stems from the bureaucratic assumption of a mechanical universe.

Smart people with Ivy League diplomas can twist dials and fly the plane of state making life better for everyone, by this logic.

It would be better in our quantum social realm if we focused on principled conditions, if we honored time-tested principles, instead of trying to outsmart human nature.

Instead of telling people how to behave, we would instruct them on what constitutes right and wrong and the consequences for them individually and for us collectively of poor conduct, based on centuries of accumulated wisdom. We would take a holistic view of broad social consequences instead of following a hollow, soulless materialism. We would extend the principle of subsidiarity to its logical conclusion and push regulation to the level of the individual as much as possible, with the caveat that there are punishments for those who deviate in ways that hurt others.

Instead, bureaucracy with its mechanical mindset centralizes regulation, assuming away all the messy edge cases. This governance handicap is encumbered further by years of rot and the accumulation of administrative barnacles.

Bureaucratic determinism and elite condescension brought us to the point of today’s political chaos, economic theory and entrenched interests be damned. The old models are broken. Their predictions are flawed.

It’s not just about trade.

If the objective function is no longer about enabling consumerism or maximizing the influence, money, and power of a thin, global, “post-national” overclass, then we’re going to see different policy choices and priorities. I have no dog in this hunt; I do not judge. Que sera, sera. I just want a better model.

Here’s George Friedman on our stochastic world and its changing data generating process:

“The model of international economics to which we are accustomed emerged from the Cold War. The economic component benefited Washington. Russia was poor and had lost much more than the United States had in World War II, while the U.S. was rich and further enriched by the war. Military power was important, but economic power was in the hands of the U.S., which shaped its economic national security to gain global power. It used trade relations to rebuild Europe to its own benefit, and in the ensuing proxy battle for the so-called Third World, it took much of the imperial territories previously held by Europe. It was a powerful tool that was necessitated by the invisible hand of geopolitics and was also predictable.

“The end of the Cold War, validated by the outcome of the war in Ukraine, has changed the status quo. U.S. solicitude toward Europe is ending, as is its concern for the Third World. This creates massive unease within the United States; the economic component of the invisible hand had been shaped by the logic of a geopolitical era that is now obsolete. And as geopolitical realities change, so too do economic realities. The decline in concern for economics as a weapon predictably reshapes U.S. economic reality, resulting in political chaos. The economic system depends on rules. Geopolitical shifts change the rules.”

All kinds of things are going to change.

Just as before, there will be winners and there will be losers.

There will be those who defend the status quo and warn of catastrophe; there will be others who have become so disenfranchised economically and morally, so disenchanted with a contemptuous elite telling them what to do and what to think, that revolutionary transformation is attractive.

The fights will be brutal.

Volatility and uncertainty will be with us for a while.

Bureaucratic institutions will not react well in this environment. They are brittle. They are weakened by years of sclerotic build-up.

Brace, brace, brace.