Dynamic Hedging

It's difficult to plan a long-term project when the regulatory environment is not stable.

When the equity markets are going up and to the right, everyone’s happy. It’s a big party. We see our friends and neighbors piling into broad market indices or narrow baskets like the Magnificent Seven or individual names. They just seem to make money.

It’s so easy a caveman can do it.

The daily returns come from an underlying statistical process. When things are working, retail investors are confident that they know what it is. The longer it works, the more they think they understand it and the surer they become that it’s here to stay.

To be fair, there are professionals who dig deep to understand what makes these statistical processes work, both at the macro level and at the level of individual securities. They possess a more informed view of the factors that drive the distribution. They know the competitive dynamics in a particular market, they assess management, they understand the differentiation of the company’s products, etc. They have models. Even some of them are susceptible to the confidence trap. Some of them may be more confident because of faith in their proprietary divining rods of profit.

For most, in practice, it’s as if the market every day pulls a ball out of a jar. The stock market’s daily return is written on this ball. Sometimes it’s positive and sometimes it’s negative. On balance, it’s positive more often than it’s negative. And the range in which the numbers appear seems to be bounded in a known range. The numbers are different every day. They are random, but they are positive, plus or minus. The plus or minus is noise. We think of it as risk or volatility. Risk is quantifiable. If the process were deterministic, then there would be no such risk. Because there is risk, we say it is stochastic.

Confidence makes the world go around. (As an aside, I recommend highly Peter Atwater’s book, The Confidence Map.)

When volatility is low, when the plus/minus is tolerable, the game appears to be even easier. Put $1 into the machine and $1.10 comes out the back at the end of the year, plus or minus, come rain or come shine. Or that’s what they think.

If people are sufficiently confident, they’ll take steps to juice their returns. They may borrow money (in one form or another) and invest it in the market if they believe that the return they’ll receive is greater than the interest they pay. They’ll say things like, “I’d do that all day.” Because confidence.

I say again. It’s so easy a caveman can do it.

Another way to boost performance is to sell volatility. In effect, they sell an insurance policy to someone else who is willing to accept a slightly lower return if it means her portfolio becomes less volatile. For the person selling protection, if you just know that hurricanes aren’t going to happen, why wouldn’t you take someone’s free money?

Here’s the thing about volatility.

Investors can handle it if behaves the way they expect. If the numbers on the balls coming out of the jar look like they were generated by the distribution of returns they imagine, then they’re happy campers.

But they start to panic if the numbers start to surprise, especially if the numbers now seem to span a broader range than what they had assumed.

They begin to worry that they were wrong about the distribution that the Market Wizard of Oz uses when he put the balls in the jar. Or, maybe, the Old Man switched the jars in the middle of the night when they weren’t paying attention. This second one we call “structural change.” Let’s say there was a virus that caused everyone to hibernate or inflation started to spread, distorting all kinds of economic decisions.

This jar instability is uncertainty. It is difficult, if not impossible, to quantify. It terrifies. You can measure risk. You cannot measure uncertainty.

Uncertainty can cause you to sell, locking in a loss, just before the new money-making regime starts afresh. From time to time, the market likes to test us. It likes to shake the tree to see who falls out.

How many people hit the bid in March of 2020, only to see the market recover without them? How many people hid in a cave after the Global Financial Crisis and missed out on the tech stock bonanza when the Fed started priming the pump?

Investing is hard. It’s incredibly hard. Hey. Anything worth doing is.

One good thing about being a small investor is that, unless the world is in really bad shape, you have liquidity: the ability to sell your positions and sit in the corner with what’s left of your cash, sucking your thumb, waiting for the thunder to stop. Sometimes markets shut down and you don’t even have that. But, at some price (and it could be terrible), you as a retail investor probably do. Even as the mob was all-in on the way up, there may be other people who instead chose to hold cash, waiting for this kind of opportunity to pounce, paying for it by foregoing the positive returns the crowd was picking up.

For the biggest players, it’s much more difficult. It may not be as easy for them to sell their mammoth positions as it was to accumulate them over time. When you invest hundreds of millions of dollars or billions of dollars, you’re managing liquidity, too. When it disappears, it’s like being a fat man with a cane at the back of a crowded theater when someone shouts “Fire!”

Some professional investors can be very good at seeing around corners, especially the older ones. They seem to have a good sense of when to take their chips off the table before the dice turn, while making the most out of a hot run.

Beware of old men in a profession where men die young. They are few and far between.

The problem that the large investor faces is similar to the context faced by someone considering developing a large multi-year project like a power plant or an oil field or a commercial real estate property.

They need to forecast their revenue and expenses for years into the future. They need to raise capital to fund the upfront expense of the project. Imagine, for example, a company that wants to build a nuclear reactor next to a new datacenter focused on AI.

How much revenue will the power plant generate from the AI datacenter? How certain is the revenue stream? Can they sign a take-or-pay contract with the datacenter or is everything going to be negotiated year-to-year? Will the customer with the datacenter generate sufficient cash flow to be able to pay your terms? Will the customer guarantee their obligation to you with other assets? Will a regulatory body determine their pricing or can they negotiate a private contract? Will they be permitted to sell excess power to the grid? If so, at what price? Will AI be regulated into something small? How will competition for the AI datacenter’s services evolve? How quickly can the power plant developer get the regulatory approvals to build the nuclear power plant? Can they hire talent easily? Will they be forced to use union labor? Where will the uranium come from and how much will it cost? What rate of return do they expect to generate? Is there a margin of safety around this estimate? How does this compare to the plant’s cost of capital?

The more certainty the developer has about the economics of the power plant, the easier it is to raise financing.

What does this have to do with bureaucracy you may ask?

Plenty. A big driver of cost and risk and uncertainty is regulation.

What happens when regulatory policy is more difficult to forecast? It becomes harder to justify long-term projects. Financing is more expensive. Ironically, even as the bureaucrat wants to see more private money ploughed into developing infrastructure, their heavy-handedness may cause capital to seek better treatment elsewhere.

We’re seeing it today.

‘On a conference call with analysts, Bédard gave the example of a green energy company spun off from General Electric, claiming GE Vernova’s wind turbine business could suffer depending on who wins after ballots are cast on Nov. 5.

‘“If it’s candidate one, he’s against windmills, so that business is going to fall. If you take the No. 2 guy, well he likes windmills, he’s more green. So that’s why we have these kinds of customers just sitting on the fence not knowing where the ball is going to drop — left or right,” Bédard said.

‘“We still anticipate this freight recession will not change probably before ’25. We have an election year in the U.S. A lot of our customers are just waiting to see what’s going to happen.”’

There is uncertainty about regulation that is affecting real decisions.

But it’s more than uncertainty. Even once there is a decision as to what the regulatory environment is going to be like for at least four years, there is no guarantee that it will stay that way. Policy is unstable. It is non-stationary. It is difficult to forecast.

Here’s the New York Times:

“The Biden administration’s move on Thursday to strictly limit pollution from coal-burning power plants is a major policy shift. But in many ways it’s one more hairpin turn in a zigzag approach to environmental regulation in the United States, a pattern that has grown more extreme as the political landscape has become more polarized.

“Nearly a decade ago, President Barack Obama was the Democrat who tried to force power plants to stop burning coal, the dirtiest of the fossil fuels. His Republican successor, Donald J. Trump, effectively reversed that plan. Now President Biden is trying once more to put an end to carbon emissions from coal plants. But Mr. Trump, who is running to replace Mr. Biden, has promised that he will again delete those plans if he wins in November.”

Why don’t you just tell me the movie you’d like to see?

It’s getting worse.

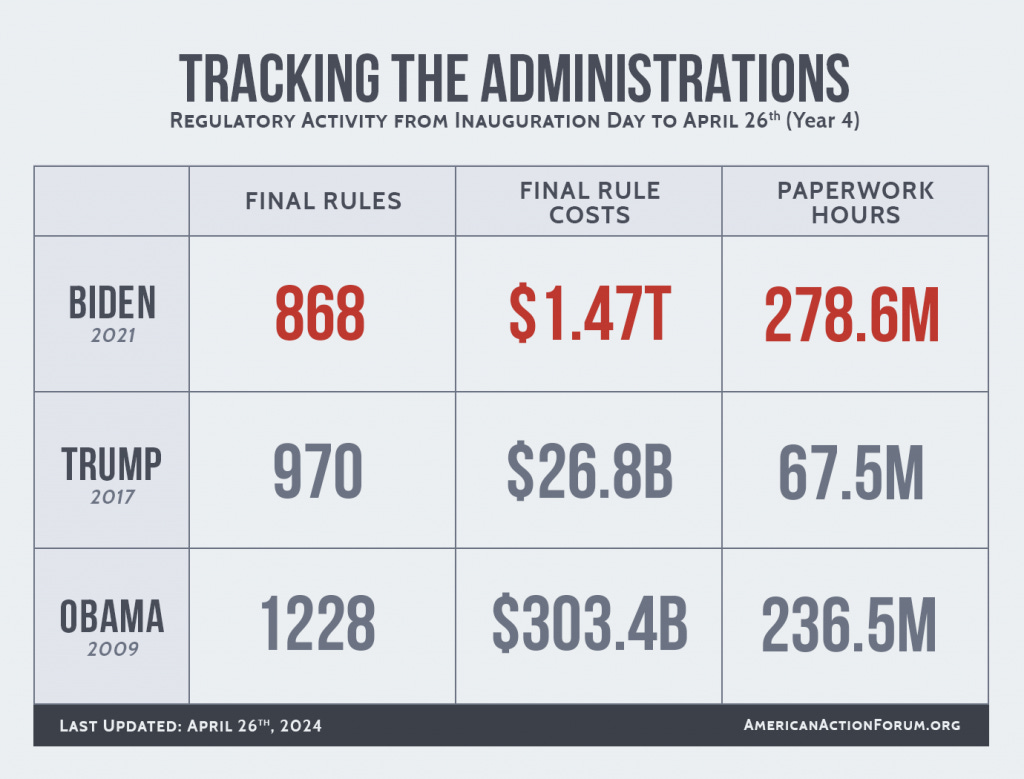

‘“In the old days, the regulatory days of my youth, we were going back and forth between the 40-yard lines,” said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, who directed the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office and now runs the American Action Forum, a conservative research organization. “Now, it’s back and forth between the 10-yard lines. They do it and undo it and do it and undo it.”’

It’s starting to have an effect.

‘“If the regulatory changes are just whiplash or snapback, it creates a level of uncertainty that makes it very hard to build a vibrant economy,” said Marty Durbin, senior vice president for policy at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the nation’s largest business lobby.

‘“It’s not about the specific regulation or the specific candidate,” Mr. Durbin said. “We’ve got to have more long-term certainty about how business is going to be regulated.”’

The swings back in forth are getting bigger and more difficult to navigate.

Combine this with higher interest rates that discount future cashflows to a greater extent and it’s not difficult to imagine a multi-industry pivot to focus the economy’s attention on shorter and shorter time spans.

Regulatory uncertainty inhibits risk-taking and long-term solutions.

When will it end?