There’s been a lot of talk about the new protectionism. Maybe, maybe too much talk. Tariffs, in particular, get a great deal of attention. The incoming Trump Administration is threatening to levy them on everyone including friends, rivals, enemies, and innocent bystanders. You get a new tariff. And you get a new tariff. And you get a new tariff.

This brings up the ghost of policy mistakes past in the approaches taken during the Great Depression such as countries competing with one another to devalue their currencies, and imposing tariffs like the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. Trade collapsed globally. There were large scale losses of production capacity. Consumption fell down an elevator shaft. It was a spiral into misery for everyone. Everyone was shooting pistols at the other guy only for the guns to explode in their own hands instead. It was what game theorists call a “negative sum game.” It was lose-lose. Everyone suffered.

The general term for this kind of failed tit-for-tat trade and industrial policy is beggar-thy-neighbor.

Today, trade imbalances are high and persistent, even as the volume of trade has grown to terrific levels.

The theory of competitive advantage seems quaint, replaced by a hall-of-mirrors distorted reality in which one country forces their high-saving citizens to subsidize the production of goods for the rest of the world. The consumers in target markets pile up hysterically large debts to purchase the cheap products, even as their own domestic industries collapse under intense competitive pressure. The emergent producing country has rules in place to limit the ability of companies from the developed country selling their products into the emergent country’s large, growing market. Emerging market leadership cites concerns about cultural contamination or institutional weakness or whatever other excuse the leaders of the emerging player can invent. None of it matters. Open, symmetric bilateral trade is off the table.

Consumption is the opium of the people.

Instead of the win-win outcome that theory dictates in which production and consumption rise in both countries, the leaders in the emerging market country have figured out a way to stage the game so that it is winner-take-all for them.

In the first phase, they use developed market consumption to build up production capacity in their own emerging market. In fact, the emerging country “over-builds” excess capacity, on a sector-by-sector basis, moving quickly up the peg board of product sophistication. They financially repress their own citizens to provide the cheap financial capital for this expansion, pillaging the excessive savings required by the absence of any kind of safety net, their directed appropriation made easier by the contrived dearth of investment alternatives. The only way to make this a two-stage game is to suppress the consumption of their own citizens.

Yesterday, our emerging market made cheap toys. Today, it’s electronics assembly. Tomorrow, it will be cutting-edge application-specific semiconductors for advanced AI.

In the second phase, once the emerging country has destroyed the competitive ability of the target developed markets to respond, one sector at a time, then the emerging market will ratchet up the prices (or restrict supply punitively). Eventually, they’ll turn their attention to build up the long-delayed consumer sensibility in their country, now the wealthiest on the planet. They have raised themselves up while bringing everyone else down. There’s a xenophobic, evil genius to their epic indifference to the welfare of their trading counterparts. If they can pull it off.

Success requires longevity. This is a one-hundred-year plan. They need to repress their own people. They need the target populations to remain pliant. They need conditions to be just right. For one hundred years. We’re forty-five years in.

If they’re successful, their improved, dynamic, two-period version of the beggar-thy-neighbor game is now a traditional win-lose game. They win. We lose. Call it what it is: mercantilism updated for the 21st century.

Is it fair? Is it equitable that the developed country’s benefits of trade in the form of a greater variety of cheaper goods should come at the cost of lost jobs, broken communities, and a growing pile of debt?

Those are the wrong questions. There is no fair or equitable. It is what it is. There’s no crying in realpolitik.

These are the conditions the West has accepted. Some people in the developed countries are in the process of rejecting this status quo. Maybe they’re too late. Go ask the German Mittelstand how to dance with the devil.

If anyone claims the current approach (one-sided, unilateral free trade) is wrong or inefficient or dangerous, you can get usual cadre of experts to chant from the free trade hymnal like monks drunk on mead. Or you can point to the always imminent threat of climate devastation or whatever other contemporary trope that seems culturally relevant. For example, when China subsidized its solar industry and destroyed the German one, we are told it was positive for the environment because it lowered the cost of production. That China is overwhelmingly dominant is just a byproduct. It’s happenstance. It’s the cost of doing business, man.

How can these policies last for so long? Well, the developed country powerful seem to benefit. They get to stay on the top shelf. Our leaders are now part of a new, unimaginably wealthy pan-global elite that has more in common with one another than they do with their constituents. The consumer likes the cheap goods. Who would push back? The people living in towns devastated by de-industrialization? They don’t have money, not anymore anyway. They don’t have influence. Who weeps for Appalachia?

Economists like Michael Pettis argue that conditions are different now. This isn’t the 1930s. It’s possible to raise tariffs and to have overall levels of consumption increase due to higher production, even as the share of consumption in the overall economy drops and savings increases. Nobody in the establishment thinks this argument has enough credibility to warrant comment. It is beneath them.

We’re about to field test this theory. That’s all we need to know. The normative questions are for university debating societies. It’s about to get real.

Let’s get back to the beggar-thy-neighbor policies and negative sum games.

Dani Rodrik has a good definition:

“A policy is beggar-thy-neighbor when the benefit provided to the domestic economy is made possible only by the harm that it generates for others. Joan Robinson coined the term in the 1930s to describe policies such as competitive devaluation, which, in a situation of generalized unemployment, shifts employment from foreign countries to the domestic economy. Beggar-thy-neighbor policies are generally negative sum for the world overall.”

If Pettis is right, the differing economic conditions of the current context could lead to an outcome in which the imposition of tariffs is a positive-sum game, especially if it forces the Chinese and other countries to stop repressing their own countrymen financially, instead implementing policies to spur domestic consumption. The Chinese leadership will do that only when it is the last remaining option. The kind of political movement that commits to one-hundred-year policies bent on global domination doesn’t deviate from the chosen path easily. A move to promote domestic consumption would be a capitulation indicative of a deeper social rot. It would signal the political weakness of the Communist regime. Strongmen don’t blink.

Let’s imagine a policy that country A takes to enhance its competitiveness. Doesn’t any change in the terms of efficiency naturally inure to the benefit of country A at the expense of its trading counterparties like country B and country C?

What if the policy that country A undertook to obtain greater efficiencies in its allocation of resources is also a policy that country B and country C can implement themselves? Country A improves its absolute efficiency, but the relative gains are muted by the catching up that B and C make happen if they match A. Everyone has greater production capacity. Everyone has greater levels of consumption. Everyone sees savings and investment increase.

This is a win-win, or a positive-sum game. It’s not beggar-thy-neighbor so much as better-thy-neighbor.

For country A’s trading partners, the truly terrifying policy scenario involves country A engaging in de-regulation/de-bureaucratization if A’s counterparts do not have the flexibility to follow.

Who cares what tariffs are? These are ephemeral numbers on an invoice. Taking steps to improve productivity permanently by eliminating bureaucracy in government and in the private sector creates persistent gains. If B and C are too stuck in their ways to match these programs, then the tariffs will be a sideshow. At some point, country A can shift the comparative advantage in its favor using tools that are more sustainable than the distortions the emerging market hegemons impose on global trade by manipulative fiat.

Once country A embarks on a course of wholesale national productivity gains, every one of its trading counterparties must consider seriously following A’s lead. They will have no choice.

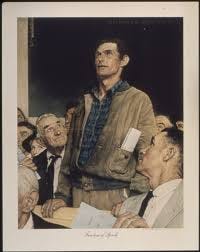

They say that courage is contagious. Liberty and efficiency are just as infectious. The pressure on other countries to dismember their bureaucracies, unleashing untold reserves of stored potential entrepreneurial energy, will be too much to oppose, at some point.

We’re already beginning to see signs of it stirring in Canada, Germany, the UK, and France.

This is a positive-sum game.

My guess is that it will spread. DOGE and its derivatives may not be 100% effective, even in the US. But the initial action may be enough to spur follow-on attempts. It may change the culture. We used to think people like us did things like that (bureaucratic sclerosis), but now we recognize that people like us are capable of doing things like this (making moonshots happen).

The winners of the next ten years may be the countries that inspire cultures of efficiency, while the losers stick to their ways.

If this hypothesis is true, it will be the biggest investment theme of the next twenty years.

What a time to be alive.